1)

When the question asks to solve for h in the equation of \(V=2\pi r^2h\), it means get h, alone, on one side of the equation. This only requires one step, in this case:

| \(V=2\pi r^2h\) | Divide by \(2\pi r^2\) on both sides of the equation. |

| \(h=\frac{V}{2\pi r^2}\) | We're done! h is by itself. |

The appropriate answer choice, therefore, is D

2) If the domain is only {2, 4, 7}, just plug them in the original equation of \(f(x)=x^2-5\).

| \(f(2)=2^2-5=-1\) | |

| \(f(4)=4^2-5=11\) | |

| \(f(7)=7^2-5=44\) | |

Now, find the answer choice that has all three of these in its domain. That would be D again.

Maxwong has the correct idea, but I think missed the criterion that states that the triangle must be acute. With this restriction, there are not as many possibilities.

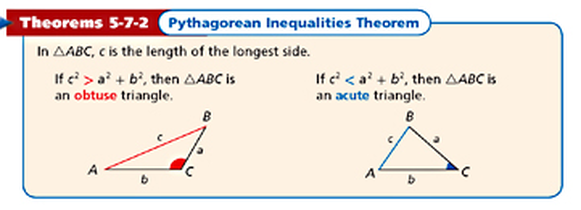

Have you ever heard of the Pythagorean Theorem? You probably have. But have you heard of the Pythagorean Inequalities Theorem? Maybe you have and maybe you haven't. I think my textbook summarizes the concept nicely and in a way that is fairly straightforward:

Source: http://abcpluspstudyguide.weebly.com/uploads/9/7/2/8/9728626/9817374.png?581

Of course, we seek triangles that only abide to acute triangles. We know 2 side lengths: 8 and 15. The remaining side I have labeled as s. Of course, there are 2 cases that are possible with s. Either it is the largest side or it is not. We will have to take both into account to solve this prolem:

For the first example, I will assume that s is the longest side, which corresponds to c in the picture above. Now, let's solve:

| \(c^2 | s is c. Whichever side you plug in for a and b does not matter. | ||

| \(s^2<8^2+15^2\) | Simplify the right hand side of the inequality to solve for s | ||

| \(s^2<64+225\) | |||

| \(s^2<289\) | Take the square root of both sides. | ||

| \(|s|<17\) | In an inequality, the absolute value has the following rule\(|a| . Now, let's apply it. | ||

| One inequality is already done. Divide both sides by -1 to get the other answer. Don't forget to flip the inequality sign! | ||

| We can clean up this solution by recognizing that we can represent the solutions as a compound inequality. | ||

| \(-17 | |||

Now, let's solve for s when is not the longest side:

| \(c^2 | This time, when we substitute, b will be in either a or b. | ||

| \(15^2 | Simplify both sides. | ||

| \(225 | SUbtract 64 on both sides. | ||

| \(161 | Take the square root of both sides. | ||

| \(\sqrt{161}<|s|\hspace{1mm}\text{or}\hspace{1mm}|s|>\sqrt{161}\) | The same logic applies for greater than symbols, too. In other words, \(|a|>b\rightarrow a>b\hspace{1mm}\text{and}\hspace{1mm} -a>b\) | ||

| Just like above, divide by -1 on the right inequality. | ||

| These inequalities cannot be combined into a compound inequality, unfortunately. | ||

The triangle must adhere to both conditions of \(-17 and ( \(s>\sqrt{161}\) or \(s<-\sqrt{161}\) )

Let's think about this logicall before our head explodes, though! If s is less than 17 and greater than √161, that means the following compound inequality arises:

\(\sqrt{161}

We don't care about the other inequality as it contains negative numbers, and negative numbers are nonsensical in the context of this problem, so I have excluded them. We aren't done yet! We have to figure out the first integer that is greater that 161. Well, \(\sqrt{161}\) is in between 12 and 13, so 13 is the first integer that is allowable under our given conditions.

Therefore, the only possible integer solutions are 13, 14, 15, and 16.

In the second question, Cphill interpreted it correctly, but if you meant \(R(x)=\frac{3x-3}{x^2-4}\) or \(R(x)=3x-\frac{3}{x^2-4}\), the answer is different. Let's think about what we have to do to figure out the vertical asymptote.

In both cases, we have rational fractions. Of course, we can't have a denominator of 0. This means that if we plug in a value for x that results in a denominator that equals 0, then it is officially outside of the domain. Let's figure out when x^2-4=0.

| \(x^2-4=0\) | You might notice that x^2-4 is a difference of 2 squares, but we don't need to take advantage of this, actually. This is because we have no b-term. Add4 to both sides. |

| \(x^2=4\) | Take the square root of both sides. |

| \(x=\pm2\) | |

This means that the vertical asymptote is at \(x=\pm2\), which corresponds to the answer choice of C.

I have already answered this question. It was posted. Then, it disappeared into the stratosphere. That's strange.

In any case, usually, this expression would be in its simplified form already. However, in this case, the radicands (numbers inside of the radical) happen to be perfect squares, so this expression can be simplified further:

| \(2\sqrt{4}+5\sqrt{9}\) | \(\sqrt{4}=2\hspace{1mm}\text{and}\hspace{1mm}\sqrt{9}=3\) |

| \(2*2+5*3\) | Now, it is a matter of simplifying from here. |

| \(4+15\) | |

| \(19\) | |

No, the expression evaluates to 39:

| \(3\left[\frac{30-8}{2}+2\right]\) | Do 30-8 first. |

| \(3\left[\frac{22}{2}+2\right]\) | Do 22/2 next. Luckily, 2 divides into 22 evenly. |

| \(3\left[11+2\right]\) | Do 11+2 after that. |

| \(3[13]=3*13=39\) | |

I'll help you simplfy this expression \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-6\left(2-\frac{2}{3}\right)\):

| \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-6\left(2-\frac{2}{3}\right)\) | To abide to order of operations, I will start with the parentheses 2-(2/3). |

| \(\frac{2}{1}-\frac{2}{3}\) | In order to subtract fractions, we must establish a common denominator. Currently, this isn't the case. To do that, we must figure out the LCM (lowest common multiple) of the denominators. In this case, one of the denominators is 1. That means that the LCM is whatever the other number is. The LCM is 3. Let's convert the fraction |

| \(\frac{2}{1}*\frac{3}{3}=\frac{6}{3}\) | Note that I am really multiplying the fraction by 1, so I am not changing the value of the fraction. |

| \(\frac{6}{3}-\frac{2}{3}=\frac{4}{3}\) | Of course, when subtraction fractions, you only subtract the numerator. |

| \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-6*\frac{4}{3}\) | Yet again, to abide by the rules of the order of operations, I will now do the exponent. I will apply the rule that \(\left(\frac{a}{b}\right)^n=\frac{a^n}{b^n}\) |

| \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2=\frac{1^2}{2^2}=\frac{1}{4}\) | I just applied the rule that I mentioned before. |

| \(\frac{1}{4}-6*\frac{4}{3}\) | Now, I will do the multiplication of 6*(4/3) |

| \(\frac{6}{1}*\frac{4}{3}=\frac{24}{3}=8\) | This is the multiplication done now. Now, we can move on to the next step. |

| \(\frac{1}{4}-8\) | Yet again, manipulate 8 such that there are common denominators. |

| \(\frac{8}{1}*\frac{4}{4}=\frac{32}{4}\) | |

| \(\frac{1}{4}-\frac{32}{4}\) | Do the subtraction. |

| \(-\frac{31}{4}=-7\frac{3}{4}\) | |

Therefore, \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-6\left(2-\frac{2}{3}\right)=-\frac{31}{4}=-7\frac{3}{4}\)

.